Amy Tan is one of the authors that has impressed me most in 2017. After reading her "The Joy Luck Club", I will definitely check her other novels. Below you have the text of the presentation of our December meeting, which is a compilation of different artilcles (links to those you can find at the very bottom).

BIOGRAPHY

Amy lives with her husband, Louis DeMattei and their two dogs, Yorkshire terriers, Bubba and Lilliput in California and New York.

|

| "I live with thoughts of being killed every day. I'm not so much afraid of death as of violence; and my mother's warnings are fulfilled - people die, terrible things can happen." |

BIOGRAPHY

Amy

Tan, whose Chinese name, An-mei, means "blessing from America,"

was born in 1952 in Oakland, California, the middle child and only

daughter of John and Daisy Tan, who came to America from China in the

late 1940s. Besides Amy, the Tans also had two sons — Peter, born

in 1950, and John, born in 1954.

Her

father was a Chinese-born Baptist minister; her mother was the

daughter of an upper-class family in Shanghai, China. Throughout much

of her childhood, Tan struggled with her parent's desire to hold onto

Chinese traditions and her own longings to become more Americanized.

Her parents wanted Tan to become a neurosurgeon, while she wanted to

become a fiction writer.

|

| 1959, Easter |

Tan

discovered that her own grandmother had been raped as a young widow

by a merchant who had forced her into concubinage; she killed herself

by swallowing raw opium. Her daughter, Daisy - Amy's mother - was

forced into a feudal marriage, but later ran away from her abusive

husband, blaming him for the deaths of two of her five children.

Leaving her husband without a divorce was a criminal act - let alone

leaving him for another man, as she did.

John

Tan, her second husband, was an electrical engineer from Beijing - he

fled the country for the US; Daisy was captured, raped and thrown

into jail - her trial, says Tan, was covered in the Shanghai tabloids

- before she, too, was able to escape to California and join him.

Daisy left China expecting to send for her three daughters, but they

were trapped once the "bamboo curtain" came down. It was 30

years before she saw them again, and for many years she never spoke

of them to her new family.

Safe

in the US, both John and Daisy toiled at night school. "From

when I was seven," recalls Tan, "my mother was a nurse,

doing everything from changing bedpans to giving vaccinations, which

is amazing to me; how she managed to cook incredible meals every

night. Everything was fresh - which I hated. 'Why can't we have

canned spinach?'" Tan wags her head brattishly. "'Fresh

vegetables are what poor people eat.'"

|

| At the age of 12 |

Tan,

who when she was young fantasised about plastic surgery to make her

look less oriental, blamed her unhappiness as a child on being

Chinese - "It was the most convenient scapegoat" - but now

feels that the constant uprooting, between 10 cities around the San

Francisco Bay area, was as much a cause of alienation. "I'd lose

a set of friends, and spend months before I'd find others. All

children have their forms of unhappiness, and being different is an

anxiety, especially as a teenager." The 50s and 60s were also an

era of assimilation: "Being different was less tolerated; you'd

be teased with racial jokes. People found it disgusting if you ate

fish with the head still attached to it. Teenagers can be very

cruel."

Brought

up bilingual (in her dreams, she speaks fluent Mandarin), Tan was

soon refusing to speak Chinese in public. She became an interpreter

for her mother, of whose imperfect English she was ashamed. "It's

something I resented as a child," she recalls, "though you

can look at it with humour. I'd be on the telephone to banks as a

young girl, pretending I was my mother. A lot of what I translated

had to do with how terrible I was - writing letters to my mother's

friends saying she was thinking of sending me to school in Taiwan to

turn me into a better girl. I learnt to say what I thought people

wanted to hear."

The

family moved nearly every year, living in Oakland, Fresno, Berkeley,

and San Francisco before settling in Santa Clara, California. They

changed houses 12 times. Although John and Daisy rarely socialized

with their neighbors, Amy and her brothers ignored their parents'

objections and tried hard to fit into American society. "They

wanted us to have American circumstances and Chinese character,"

Tan said in an interview with Elaine Woo in the Los Angeles

Times (March 12, 1989).

Young

Amy was deeply unhappy with her Asian appearance and heritage. She

was the only Chinese girl in class from the third grade until she

graduated from high school. She remembers trying to belong and

feeling frustrated and isolated. "I felt ashamed of being

different and ashamed of feeling that way," she remarked in

a Los Angeles Times interview. In fact, she was so

determined to look like an American girl that she even slept with a

clothespin on her nose, hoping to slim its Asian shape. By the time

Amy was a teenager, she had rejected everything Chinese. She even

felt ashamed of eating "horrible" five-course Chinese meals

and decided that she would grow up to look more American if she ate

more "American" foods. "There is this myth," she

said, "that America is a melting pot, but what happens in

assimilation is that we end up deliberately choosing the American

things — hot dogs and apple pie — and ignoring the Chinese

offerings" (Newsweek, April 17, 1989).

Amy's

parents had high expectations for her success. They decided that she

would be a full-time neurosurgeon and part-time concert pianist. But

they had not reckoned with her rebellious streak. Ever since she won

an essay contest when she was eight years old, Amy dreamed of writing

novels and short stories. Her dream seemed unlikely to become

reality, however, after a series of tragedies shook her life. When

she was 14, Tan experienced the loss of both her father and her

sixteen-year-old brother Peter to brain tumors and learned that two

sisters from her mother's first marriage in China were still alive.

An

episode of child molestation in The Bonesetter's Daughter echoes

something that happened to Amy Tan herself. "My brother was

dead, my father was in the hospital and had lost his mind; he almost

didn't recognise me. I'd been a Daddy's girl - my father was

brilliant, personable; he was the one I wanted to be like. To see him

there, laughing because he was demented . . ." she trails off.

She

was being counselled by a community elder because her mother thought

she was out of control. "The man said, 'Your father's in a lot

of physical pain; he'd be in even more pain knowing what you're

doing.' I'd been this hard-shelled, defiant teenager, not showing

that anything mattered to me. But I broke down sobbing. I was

hysterical with grief." Then the man changed tack: "He

started to tickle me, threw me on to the bed and moved to other parts

of my body. It felt so wrong, but I thought, how can it be? This man

is a respected member of the community."

The

man, whom Tan declines to name to this day ("I'm so afraid he'll

come back into my life"), reappeared years later at one of her

book signings. "I was like a deer caught in headlights,"

she says. "I could not speak."

Deciding

that the remaining family needed to escape from the site of their

tragedy, Daisy settled with Amy and her brother in Montreux,

Switzerland. at

her private school, Tan says, she was nearly raped by a school

janitor. "The teachers told me, next time, you should be more

careful." They sacked the man. "I lived in terror he would

come after me and kill me."

The

move intensified Amy's rebellion. "I did a bunch of crazy

things," she told Elaine Woo. "I just kind of went to

pieces." Perhaps the most dangerous was her relationship with an

older German man who had close contacts with drug dealers and

organized crime. Daisy had the man arrested for drug possession and

got her daughter hauled before the authorities. Amy quickly severed

all ties with the German.

A

year later, Daisy, Amy, and John returned to San Francisco. In 1969,

Amy enrolled in Linfield College, a small Baptist university in

McMinnville, Oregon. Daisy selected the college because she believed

it to be a safe haven for her daughter. A year later, however, Amy

followed Louis DeMattei, her Italian-American boyfriend, to San Jose

City College in California. Just as distressing to Daisy, Amy changed

her major from pre-med to English and linguistics. Daisy was so upset

that she and her daughter did not speak to each other for six months.

Amy

then transferred to San Jose State University and earned a B.A. in

English and an M.A. in linguistics. After completing her degrees, Amy

married DeMattei, a tax attorney. Still not certain what path to

pursue, she entered a doctoral program in linguistics at the

University of California at Santa Cruz and at Berkeley, but left in

1976 to become a language-development consultant for the Alameda

County Association for Retarded Citizens. It was not until the early

1980s that she became a business writer.

A college roommate was murdered while Tan was studying for a PhD at

Berkeley. "I had to identify the body and go in the room and see

all the blood," she remembers with horror. "It happened on

my birthday, and every year for about 10 years, on my birthday I lost

my voice."

She

worked as a language development specialist for county-wide programs

serving developmentally disabled children, birth to five, and later

became director for a demonstration project funded by the

U.S. Department of Education to mainstream multicultural children

with developmental disabilities into early childhood programs. In

1983, she became a freelance business writer, working with

telecommunications companies, including IBM and AT&T.

As

with all fairy tales, The Joy Luck Club had an

unlikely beginning. Tan's business writing venture was so successful

that she was able to buy her mother a house. Yet, despite her

happiness at being able to provide for her mother, she was not

fulfilled in her work. "I measured my success by how many

clients I had and how many billable hours I had," she told

interviewer Jonathan Mandell. Secretly, Tan had always wanted to

write fiction, but she had thrown herself so completely into her

freelance career that she spent more than ninety hours a week at it.

Early in 1985, Tan began to worry that she was devoting too much time

to her business and started looking for a change. She decided to

force herself to do another kind of writing. The turning point came a

year later, when Tan's mother was hospitalized after a heart attack.

"I decided that if my mother was okay, I'd get to know her. I'd

take her to China, and I'd write a book." Her only previous

forays into fiction were "vacation letters written to friends in

which I tried to create little stories based on things that happened

while I was away," she noted.

|

| Tan learned her mother's true maiden name - Li Bingzi - on the day her mother died. "I was stunned; I'd spent all these years writing about her life, but I didn't know what name she was born with." |

Her

first story was published in 1986 in a small literary

magazine, FM

Five, which

was then reprinted in Seventeen

and Grazia.

Literary

AgentSandy Dijkstra read her early work and offered to serve as

her agent, even though Amy asserted she had no plans to pursue a

fiction writing career. In 1987, Amy went to China for the

first time, accompanied by her mother. When she returned home,

she learned that she had received three offers for a book of

short stories, of which only three had been written. The

resulting book, The

Joy Luck Club, was

hailed as a novel and became a surprise bestseller, spending

over forty weeks on the New York Times Bestseller List.

The

same year, Tan wrote a short story, "Endgame," about a

brilliant young chess champion who has a difficult relationship with

her overprotective Chinese mother. Tan expanded the story into a

collection, and it was sold to the prestigious publisher G.P. Putnam.

Because of her huge advance — $50,000 — Tan dissolved her

freelance business and completed the volume, which she named The

Joy Luck Club. "I wrote it very quickly because I was

afraid this chance would just slip out of my hands," she told

Elaine Woo. She completed the manuscript in May 1988, and the book

was published the following year. The book was greeted with almost

universal acclaim. "Magical," said fellow novelist Louise

Erdrich; "intensely poetic and moving," echoed Publishers

Weekly. "She has written a jewel of a book,"

Orville Schell concluded in the New York Times (March

19, 1989).

Her

first novel, The Joy Luck Club, was published in 1989 when she was

37, remained on the New York Times bestseller list for 77 weeks

In

April 1989, The Joy Luck Club made the New

York Times' bestseller list, where it remained for seven

months. Tan was named a finalist for the National Book Award for

fiction and National Book Critics Circle Award. She received the Bay

Area Book Reviewers Award for fiction and the Commonwealth Club Gold

Award. Paperback rights for the novel sold for more than $1.23

million, and it has been translated into seventeen languages,

including Chinese.

The

phenomenal success of The Joy Luck Club and the

unfamiliar rituals of being a celebrity made it difficult for Tan to

concentrate on writing her second novel. At one time, writing it

became such a challenge that she broke out in hives. She began seven

different novels until she hit upon a solution: "When my mother

read The Joy Luck Club," Tan said, "she was

always complaining to me how she had to tell her friends that, no,

she was not the mother or any of the mothers in the book. . . . So

she came to me one day and she said, 'Next book, tell my true

story.'"

The

Kitchen God's Wife, published in 1991, tells the story of

Daisy's life through the fictional Winnie, a refugee from China. The

book was a huge success even before publication: in a tightly fought

contest, the Literary Guild bought the book club rights for a

reported $425,000. Five foreign publishers bought rights to the novel

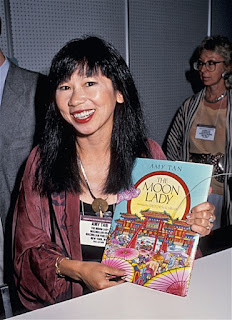

— all before publication. In 1992, Tan published a children's

book, The Moon Lady. The plot is taken from the

"Moon Lady" episode in The Joy Luck Club. "The

haunting tale that unfolds is worthy of retelling," Publishers

Weekly wrote.

Amy

served as Co-producer and Co-screenwriter with Ron Bass for the

film adaptation of "The Joy Luck Club," for which they

received WGA and BAFTA nominations. She was the Creative

Consultant for "Sagwa," the Emmy nominated PBS

television series for children, which has aired worldwide, including

in the UK, Latin America, Hong Kong, China, Taiwan, and Singapore.

Her story in The

New Yorker, “Immortal

Heart,” was performed on stages throughout the U.S. and in France.

Her essays and stories are found in hundreds of anthologies and

textbooks, and they are assigned as required reading in many high

schools and universities. She was the guest editor for Best

American Short Stories 1999. She

appeared as herself in the animated series The Simpsons. She

performed as narrator with the San Francisco Symphony playing an

original score for Sagwa, by composer Nathan Wang. Amy Tan

has been nominated for the National Book Award, the National Book

Critics Circle Award, and the International Orange Prize, and has won

many awards including the Commonwealth Gold Award.

Amy has lectured internationally at universities, including Stanford, Oxford, Jagellonium, Beijing, and Georgetown both in Washington, DC and Doha, Qatar. She has delivered a TED talk and spoken at the White House, appeared on the popular NPR program Wait Wait…Don’t Tell Me, as well as on Sesame Street on Public Television. The National Endowment for the Arts chose The Joy Luck Club for its 2007 Big Read program.

Amy also wrote the libretto for The Bonesetter’s Daughter, which had its world premiere with the San Francisco Opera in September 2008.

Amy has lectured internationally at universities, including Stanford, Oxford, Jagellonium, Beijing, and Georgetown both in Washington, DC and Doha, Qatar. She has delivered a TED talk and spoken at the White House, appeared on the popular NPR program Wait Wait…Don’t Tell Me, as well as on Sesame Street on Public Television. The National Endowment for the Arts chose The Joy Luck Club for its 2007 Big Read program.

Amy also wrote the libretto for The Bonesetter’s Daughter, which had its world premiere with the San Francisco Opera in September 2008.

The

Bonesetter's Daughter, was conceived in response to the diagnoses,

within a few months of each other, of her mother Daisy with

Alzheimer's and her friend and editor, Faith Sale, with cancer. They

both died within a few onths in 1999.

The

book Fate! Luck! Chance! Amy Tan, Stewart Wallace, and the

Making of The Bonesetter’s Daughter, by Ken Smith, was published by

Chronicle Books in August 2008, and a documentary about the

opera, Journey of the Bonesetter's Daughter, premiered on

PBS in 2011.

Amy Tan has served as lead rhythm “dominatrix,” backup singer, and second tambourine with the literary garage band, the Rock Bottom Remainders, whose members included Stephen King, Dave Barry, and Scott Turow. Their yearly gigs raised over a million dollars for literacy programs. To honor her support of zoological field research, her name was given to a newly discovered species of terrestrial leeches, Chtonobdela tanae, the first soft-bodied microscopic organism to be identified using a new method of computed tomography. In keeping with her love of science in the wild and childhood love of doodling, she recently took up nature journal sketching.

Amy Tan has served as lead rhythm “dominatrix,” backup singer, and second tambourine with the literary garage band, the Rock Bottom Remainders, whose members included Stephen King, Dave Barry, and Scott Turow. Their yearly gigs raised over a million dollars for literacy programs. To honor her support of zoological field research, her name was given to a newly discovered species of terrestrial leeches, Chtonobdela tanae, the first soft-bodied microscopic organism to be identified using a new method of computed tomography. In keeping with her love of science in the wild and childhood love of doodling, she recently took up nature journal sketching.

|

| with Stephen King |

Amy lives with her husband, Louis DeMattei and their two dogs, Yorkshire terriers, Bubba and Lilliput in California and New York.

|

| with her husband at Obama's reception ball |

When

not writing, she enjoys playing pool. She is a frequent visitor to

Family Billiards in San Francisco.

THE JOY LUCK CLUB

It was not until the 1976 publication of Maxine Hong Kingston's mystical memoir of her San Francisco childhood, The Woman Warrior, that Asian-American writers broke into mainstream American literature. Even so, ten more years had to pass until another Asian-American writer achieved fame and fortune. The Joy Luck Club, Amy Tan's first novel, sold an astonishing 275,000 hard-cover copies upon its 1989 publication. The success of Tan's book increased publishers' willingness to gamble on first books by Asian-American writers.

The Joy Luck Club describes the lives of four Asian women who fled China in the 1940s and their four very Americanized daughters. The novel focuses on Jing-mei "June" Woo, a thirty-six-year-old daughter, who, after her mother's death, takes her place at the meetings of a social group called the Joy Luck Club. As its members play mah jong and feast on Chinese delicacies, the older women spin stories about the past and lament the barriers that exist between their daughters and themselves. Through their stories, Jing-mei comes to appreciate the richness of her heritage.

Suyuan Woo, the founder of the Joy Luck Club, barely escaped war-torn China with her life and was forced to leave her twin infant daughters behind. Her American-born daughter, Jing-mei "June" Woo, works as a copywriter for a small advertising firm. She lacks her mother's drive and self-confidence but finds her identity after her mother's death when she meets her twin half-sisters in China.

An-mei Hsu grew up in the home of the wealthy merchant Wu Tsing. She was without status because her mother was only the third wife. After her mother's suicide, An-mei came to America, married, and had seven children. Like Jing-mei Woo, An-mei's daughter Rose is unsure of herself. She is nearly prostrate with grief when her husband, Ted, demands a divorce. After a breakdown, she finds her identity and learns to assert herself.

Lindo Jong was betrothed at infancy to another baby, Tyan-yu. They married as preteens and lived in Tyan-yu's home. There, Lindo was treated like a servant. She cleverly tricked the family, however, and gained her freedom. She came to America, got a job in a fortune cookie factory, met and married Tin Jong. Her daughter, Waverly, was a chess prodigy who became a successful tax accountant.

Ying-ying St. Clair grew up a wild, rebellious girl in a wealthy family. After she married, her husband deserted her, and Ying-ying had an abortion and lived in poverty for a decade. Then she married Clifford St. Clair and emigrated to America. Her daughter, Lena, is on the verge of a divorce from her architect husband, Harold Livotny. She established him in business and resents their unequal division of finances.

Introduction to the Book Amy Tan's The Joy Luck Club was written as a collection of short stories, but the tales of memory, fate, and selfdiscovery interlock to create a colorful mural that reads like a novel. All four sections open with a Chinese fable, then shift to the stories of four pairs of mothers and daughters. The tone switches from mundane to magical to darkly humorous. The tales, particularly those set in China, are by turns beautiful and harrowing. The first story begins two months after Jing-mei "June" Woo loses her mother, Suyuan, to a brain aneurysm. Her mother's best friends—June's "aunties"—invite June to take Suyuan's place at their mah jong table so she can sit at the East, "where everything begins." Suyuan Woo had invented the original Joy Luck Club in China, before the Japanese invaded the city of Kweilin. They had used the group to help shield themselves from the harshness of war. As they feasted on whatever they could find, they transformed their stories of hardship into ones of good fortune. After Suyuan reaches the United States, she resurrects the Joy Luck Club with three other Chinese émigrés, and the four reinvent themselves in San Francisco's Chinatown. These four mothers hope the mix of "American circumstances with Chinese character" will give their daughters better lives. In each section of the novel, June recounts her late mother's fantastic tales on evenings after "every bowl had been washed and the Formica table had been wiped down twice." Every time Suyuan tells her daughter about Kweilin, she invents a new ending. But one night she reveals the real ending—how she lost her twin daughters while fleeing the Japanese invasion: "Your father is not my first husband. You are not those babies." After her mother's death, June realizes that she had not fully understood her mother's past or her intentions. She journeys to China to discover what her mother had lost there. She is feverish to find out who she is, where she came from, and what future she can create—so she can finally join The Joy Luck Club.

"Before I wrote The Joy Luck Club," Tan said in an interview, "my mother told me, 'I might die soon. And if I die, what will you remember?"' Tan's answer appears on the book's dedication page, emphasizing the novel's adherence to truth. How much of the story is real? "All the daughters are fractured bits of me," Tan said in a Cosmopolitan interview. Further, Tan has said that the members of the club represent "different aspects of my mother."

It was not until the 1976 publication of Maxine Hong Kingston's mystical memoir of her San Francisco childhood, The Woman Warrior, that Asian-American writers broke into mainstream American literature. Even so, ten more years had to pass until another Asian-American writer achieved fame and fortune. The Joy Luck Club, Amy Tan's first novel, sold an astonishing 275,000 hard-cover copies upon its 1989 publication. The success of Tan's book increased publishers' willingness to gamble on first books by Asian-American writers.

The Joy Luck Club describes the lives of four Asian women who fled China in the 1940s and their four very Americanized daughters. The novel focuses on Jing-mei "June" Woo, a thirty-six-year-old daughter, who, after her mother's death, takes her place at the meetings of a social group called the Joy Luck Club. As its members play mah jong and feast on Chinese delicacies, the older women spin stories about the past and lament the barriers that exist between their daughters and themselves. Through their stories, Jing-mei comes to appreciate the richness of her heritage.

Suyuan Woo, the founder of the Joy Luck Club, barely escaped war-torn China with her life and was forced to leave her twin infant daughters behind. Her American-born daughter, Jing-mei "June" Woo, works as a copywriter for a small advertising firm. She lacks her mother's drive and self-confidence but finds her identity after her mother's death when she meets her twin half-sisters in China.

An-mei Hsu grew up in the home of the wealthy merchant Wu Tsing. She was without status because her mother was only the third wife. After her mother's suicide, An-mei came to America, married, and had seven children. Like Jing-mei Woo, An-mei's daughter Rose is unsure of herself. She is nearly prostrate with grief when her husband, Ted, demands a divorce. After a breakdown, she finds her identity and learns to assert herself.

Lindo Jong was betrothed at infancy to another baby, Tyan-yu. They married as preteens and lived in Tyan-yu's home. There, Lindo was treated like a servant. She cleverly tricked the family, however, and gained her freedom. She came to America, got a job in a fortune cookie factory, met and married Tin Jong. Her daughter, Waverly, was a chess prodigy who became a successful tax accountant.

Ying-ying St. Clair grew up a wild, rebellious girl in a wealthy family. After she married, her husband deserted her, and Ying-ying had an abortion and lived in poverty for a decade. Then she married Clifford St. Clair and emigrated to America. Her daughter, Lena, is on the verge of a divorce from her architect husband, Harold Livotny. She established him in business and resents their unequal division of finances.

Introduction to the Book Amy Tan's The Joy Luck Club was written as a collection of short stories, but the tales of memory, fate, and selfdiscovery interlock to create a colorful mural that reads like a novel. All four sections open with a Chinese fable, then shift to the stories of four pairs of mothers and daughters. The tone switches from mundane to magical to darkly humorous. The tales, particularly those set in China, are by turns beautiful and harrowing. The first story begins two months after Jing-mei "June" Woo loses her mother, Suyuan, to a brain aneurysm. Her mother's best friends—June's "aunties"—invite June to take Suyuan's place at their mah jong table so she can sit at the East, "where everything begins." Suyuan Woo had invented the original Joy Luck Club in China, before the Japanese invaded the city of Kweilin. They had used the group to help shield themselves from the harshness of war. As they feasted on whatever they could find, they transformed their stories of hardship into ones of good fortune. After Suyuan reaches the United States, she resurrects the Joy Luck Club with three other Chinese émigrés, and the four reinvent themselves in San Francisco's Chinatown. These four mothers hope the mix of "American circumstances with Chinese character" will give their daughters better lives. In each section of the novel, June recounts her late mother's fantastic tales on evenings after "every bowl had been washed and the Formica table had been wiped down twice." Every time Suyuan tells her daughter about Kweilin, she invents a new ending. But one night she reveals the real ending—how she lost her twin daughters while fleeing the Japanese invasion: "Your father is not my first husband. You are not those babies." After her mother's death, June realizes that she had not fully understood her mother's past or her intentions. She journeys to China to discover what her mother had lost there. She is feverish to find out who she is, where she came from, and what future she can create—so she can finally join The Joy Luck Club.

"Before I wrote The Joy Luck Club," Tan said in an interview, "my mother told me, 'I might die soon. And if I die, what will you remember?"' Tan's answer appears on the book's dedication page, emphasizing the novel's adherence to truth. How much of the story is real? "All the daughters are fractured bits of me," Tan said in a Cosmopolitan interview. Further, Tan has said that the members of the club represent "different aspects of my mother."

The

novel traces the fate of four mothers — Suyuan Woo, An-mei Hsu,

Lindo Jong, and Ying-ying St. Clair — and their four daughters —

Jing-mei "June" Woo, Rose Hsu Jordan, Waverly Jong, and

Lena St. Clair. All four mothers fled China in the 1940s and retain

much of their heritage. All four daughters are very Americanized. As

Tan remarked, the club's four older women represent "different

aspects of my mother, but the book could be about any culture or

generation and what is lost between them."

The four older women have experienced almost inconceivable horrors early in their lives. Suyuan Woo was forced to abandon her infant daughters in order to survive in a war-torn land; An-mei Hsu sees her mother commit suicide in order to enable her daughter to have a future. Lindo Jong is married at twelve to a child to whom she was betrothed in infancy; Ying-ying St. Clair was abandoned by her husband, had an abortion, and lived in great poverty for a decade. She then married a man whom she did not love, a man she could barely communicate with despite their years together.

By comparison, the four daughters have led relatively blessed lives, cosseted by their doting — if assertive — mothers. Ironically, each of the daughters has great difficulty achieving happiness. Waverly Jong divorces her first husband, and both Lena St. Clair and Rose Hsu Jordan are on the verge of splitting with their husbands. Lena is wretchedly unhappy and considering divorce; Rose's husband, Ted, has already served the divorce papers. Jing-mei has never married nor has she a lover. Furthermore, none of the daughters is entirely comfortable when dealing with the events of her life. Although she has achieved great economic success as a tax accountant, Waverly is afraid to tell her mother that she plans to remarry. Lena has a serious eating disorder, and she bitterly resents the way that she and her husband, Harold, split their finances, and how her career has suffered in order to advance his. Rose suffers a breakdown when her husband moves out. She lacks self-esteem, and her mother cannot understand why she sobs to a psychiatrist rather than asserting herself. Jing-mei is easily intimidated, especially by her childhood friend Waverly. She is not satisfied with her job as an advertising copywriter, and, like Rose, she lacks self-esteem.

Through the love of their mothers, each of these young women learns about her heritage and so is able to deal more effectively with her life.

The four older women have experienced almost inconceivable horrors early in their lives. Suyuan Woo was forced to abandon her infant daughters in order to survive in a war-torn land; An-mei Hsu sees her mother commit suicide in order to enable her daughter to have a future. Lindo Jong is married at twelve to a child to whom she was betrothed in infancy; Ying-ying St. Clair was abandoned by her husband, had an abortion, and lived in great poverty for a decade. She then married a man whom she did not love, a man she could barely communicate with despite their years together.

By comparison, the four daughters have led relatively blessed lives, cosseted by their doting — if assertive — mothers. Ironically, each of the daughters has great difficulty achieving happiness. Waverly Jong divorces her first husband, and both Lena St. Clair and Rose Hsu Jordan are on the verge of splitting with their husbands. Lena is wretchedly unhappy and considering divorce; Rose's husband, Ted, has already served the divorce papers. Jing-mei has never married nor has she a lover. Furthermore, none of the daughters is entirely comfortable when dealing with the events of her life. Although she has achieved great economic success as a tax accountant, Waverly is afraid to tell her mother that she plans to remarry. Lena has a serious eating disorder, and she bitterly resents the way that she and her husband, Harold, split their finances, and how her career has suffered in order to advance his. Rose suffers a breakdown when her husband moves out. She lacks self-esteem, and her mother cannot understand why she sobs to a psychiatrist rather than asserting herself. Jing-mei is easily intimidated, especially by her childhood friend Waverly. She is not satisfied with her job as an advertising copywriter, and, like Rose, she lacks self-esteem.

Through the love of their mothers, each of these young women learns about her heritage and so is able to deal more effectively with her life.

SOURCES:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2001/mar/03/fiction.features

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario